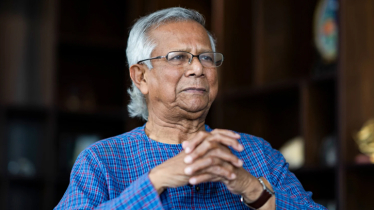

Photo : Collected

Microcredit emerged as a potent instrument for alleviating poverty in Bangladesh long ago and sparked a significant surge over the past two decades. At present, 13 ministries and divisions of the government are involved in public microcredit operations. Numerous non-governmental organisations (NGOs), including the expansive Grameen Bank, the largest NGO in the field, contribute to extending microcredits to the impoverished. Despite these efforts, the expected drastic reduction in poverty has not materialized – thereby underscoring the need for more effective implementation of microcredit operations.

A pivotal factor contributing to the less-than-desired impact of microcredit on poverty is the high interest rates associated with these credits. Ideally designed to benefit the poor or extremely poor, studies by responsible developmental agencies reveal that a significant number of microcredit recipients fall outside the impoverished category. For microcredit to be truly impactful, interest rates must be bearable, if not nominal, particularly for those in dire economic straits. Even after a 4% reduction in interest rates on official microcredit operations—from 15% to 11%—the relief among poor microcredit users remains insufficient. What is needed are nominal interest rates, ideally around 4% or 5%, to facilitate proper utilisation of credits and smooth repayment of the same.

The government’s role in this context is important. A reduction in interest rates, without compromising the viability of official microcredit operations, is imperative. The government should not be involved in extracting undue interest from the poor but rather focus on reducing poverty. Although the current government has expanded microcredit operations, efforts to make terms and conditions more affordable and lenient are still necessary to meet the intended objectives of these programmes.

NGOs, including the Grameen Bank, often charge high interest rates on microcredits, with the latter known for rates as high as 15%. These organisations must be persuaded to substantially decrease interest rates – thereby aligning their credit operations with the genuine benefit of the poor rather than profit-making.

Despite increased opportunities for the poor to access institutional microcredits, they remain vulnerable to private moneylenders or “mahajans.” Studies reveal that mahajans continue to exploit gaps in institutional credit availability. Thus, the expansion of institutional credit networks, both by the government and NGOs, should be accompanied by a significant reduction in interest rates. Furthermore, enforcing strict laws is imperative to curb the exploitative activities of mahajans, some of whom even charge interest rates as exorbitant as 300%.

Messenger/Disha