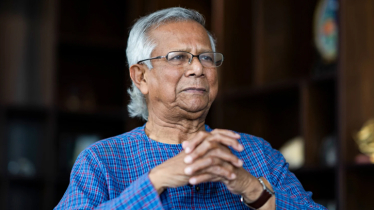

Photo: Collected

It will be very difficult to find a family that has hired a domestic-help or housemaid who is not vulnerable, exploited, abused and their rights denied. For most employers, the domestic workers are known as ‘servants’ or ‘bua’ and they are treated as slaves in urban areas.

It would be difficult to assess the population of domestic workers in Bangladesh, as there is no official headcount.

An overwhelming majority of domestic workers, preferably girl-children are even employed at the age of 7 to 10 years old and have to serve the wishes of their home-owners.

Domestic help remains vulnerable. They are hired on lowly paid jobs, long gruelling hours, exploitative working conditions and victims of abuses including torture. Wage, benefits and facilities for live-in staff are unspeakable.

Specifically, the child domestic workers are mostly non-paid employment. Most employers argue that they are supporting a child from poverty-stricken parents and cannot spare food for their child.

They boast that they have saved a child from hunger and starvation and God will surely bestow blessings to the employers.

The majority of the live-in child domestic workers lives in exploitative conditions. They are forced to sleep on the floors in a kitchen or store room.

The meals offered are discriminatory. They eat from the leftovers. No time to rest and watch television. No off-days and not to speak of overtime.

Hundreds of cases reported by NGOs working as domestic maids were sexually violated. When the female domestic-help becomes pregnant, they are fired with an excuse of stealing or blame her for secretly maintaining a boyfriend who was responsible for the pregnancy.

Unfortunately in Bangladesh, domestic-help lacks legal protection and workers’ rights. A nine-year-old policy to safeguard the vulnerable working population has yet to be implemented and there are no separate laws to protect domestic workers’ rights.

Another difficulty which was raised by the government is that a child under 18 cannot be bracketed as a domestic worker. The Labour Act amended in 2023 has not included domestic workers in the categories of workers, writes an online English news portal.

NGOs working with disadvantaged children argue that if those under 18 domestic workers are left out of the law, they would be exploited, abused and denied their rights. The owners would enjoy impunity through the loopholes of the law.

As a result, a combination of blind spots in legislation, a weak application of existing laws and a culture that undervalues domestic work has left migrant domestic workers vulnerable and at the margins of society. As a result, they often face low pay, grueling hours and exploitative working conditions. Authorities concerned should immediately look into this.

Messenger/Disha