Photo: Messenger

June 1971. After writing the last paragraph of the novel, he folded his pen and stood up from the chair. There was a gunshot outside. Enemy occupied country. At any time, at any moment, you can become a corpse, with one shot. Life and death are at the feet. He wrote the last line, 'New man, new identity and a new light. How far is he? Can't be too far. Just this night. It will be cut.' The expression of the wish and expectation of the writer and seven and a half crore Bengalis at that time. His last sentence must have been cut off. A blood red sun rose in the eastern horizon after nine months of continuous fighting. From April to June 1971, he could not see the results of his hard work for three consecutive months in the library. Writing a novel about a nation's desire to win a war while sitting on the battlefield was not an easy task. At any time enemies could come and drag him away while composing. But no, it didn't happen. But he was taken blindfolded by his own students, who became companions of the enemy and became drunk on killing their own countrymen. He was a teacher by profession. Wrote research, short stories, novels, poems, essays – all. But sitting on the battlefield, he wrote that invaluable document in the first three months of the war. There is the exploitation, deprivation, oppression of the Bengali nation and the motivation to break free from it and win the war.

In June, he witnessed the dawn of liberation. In April, when he commenced writing the novel, the first sentence emerged, 'Bangladeshe Namal Bhor' (Dawn in Bangladesh). However, this morning was not just any morning; it marked both the beginning and end of the massacre orchestrated by the Pakistani invaders in operation searchlight on the night of March 25. Gunshots reverberated throughout the night, instilling fear but not claiming lives.

The martyr, Professor Anwar Pasha, driven by self-realisation, made a solemn commitment to chronicle the Bengali liberation war in the form of a novel. He initiated the narrative by vividly describing the dawn that followed the night of March 25, a moment etched in the history of Bangladesh. Among the wartime literature of that era, his work 'Rifle Roti Aurat' stands as a unique testimony. Through the lens of a university teacher seated on the battlefield, he meticulously narrated the unfolding events of every moment. Painting scenes of death and horror while standing amidst the imminent threat of mortality is an arduous task, but Anwar Pasha, propelled by love for his country and a sense of responsibility to the nation, accomplished it with remarkable skill.

It can be asserted that future generations in Bengal, as they inherit and read this unadulterated document, will be profoundly moved by one of the saddest and cruelest chapters in the history of this country. They will grasp the unprecedented example of self-sacrifice and patriotism, a legacy that naturally evokes pride. Anwar Pasha's ability to craft such a narrative, unfazed while facing the imminent threat of gunfire in invaded Bangladesh, is truly unimaginable.

The book's narrative confines itself to the tragic experiences of the harrowing days of March 1971 and the dark period of the first half of April. However, its resonance and significance extend well before and after this timeframe. By sacrificing his own life, Anwar Pasha infused the narrative of his novel with blood. The central character of the book is Sudipta Shahin, an English Department teacher at Dhaka University. Essentially, he embodies the essence of Anwar Pasha himself.

On March 25 and 26, Sudipta experienced what felt like not merely two nights but two distinct epochs—the embodiment of Pakistan's dual eras. These periods epitomized the contrasting facets of Pakistani perspectives towards Bangladesh: governance and exploitation. Regardless of the nature of Bengal, the approach remained consistent—rule and exploit. In the face of resistance, intensify control; if absorption proves challenging, tighten the grip with more stringent rule. When the rule of law faltered, resort to the harsh measures of rifle and cannon-machine gun governance.

Sudipta endured a night of relentless artillery and machine gun attacks, making death appear palpable and easily attainable. However, inexplicably, he survived. The ease with which countless others succumbed to fate that day was a path Sudipta could not tread. Death, it seemed, was not destined for him on that fateful day.

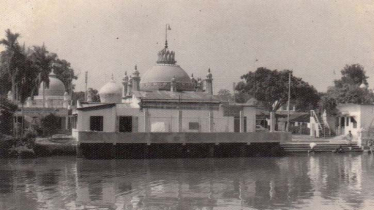

His contemplation now centers on the realisation that dying is no simple feat. Yet, fate had a different plan for Sudipta and Anwar Pasha—they did not meet their end on the night of March 25. Instead, they met their tragic demise at the hands of assassins on December 14. The Al-Badar forces forcibly extracted Sudipta from his residence, blindfolded and bound, along with Anwar Pasha, his former student. They were taken to the Torture Cell of Teachers Training College, where they experienced brutal torment before succumbing to death. Their lifeless bodies were callously abandoned at Rayerbazar Slaughterhouse. On the night of March 25, when the invading Pakistani forces launched their attack on the students' residence hall and teachers' quarters of Dhaka University, Anwar Pasha, a Bengali teacher at Dhaka University, miraculously survived.

Anwar Pasha was born in Kazisha village of Murshidabad. He completed his Bachelor's degree from Rajshahi College and his Master's degree from the University of Calcutta. In 1958, he started teaching at Pabna Edward College. In 1966, he joined the Bengali department at the University of Dhaka. He continued working in this department until his untimely death at the age of only 43 when he was assassinated. Despite not being actively involved in politics, he supported the Congress.

In 1964, during the communal riots in Pabna, he actively resisted the violence and saved 30 Hindu students. Despite facing communal forces, he could not save himself when assailants took his life.

He was the son of Muslim parents but, in his novels, he depicted the perception of Pakistani Muslims towards Bengalis. He quoted Dr. Abdul Khalek, a Pakistani teacher, in a conversation, portraying the Pakistani attitude towards Bengalis: "Your situation, Bengalis, is like a caged bird. For a long time, you were nourished in the cage of Hinduism. Even now, after leaving, you can't fly. It means you cannot give up Hinduism."

Pakistanis never accorded the dignity of being true Muslims to Bengali Muslims. The conversation reveals the character of Pakistani nationalism: "Before the unity of Pakistan, there is our armed forces. This armed force is the asset of our pride and honor. At any cost, they will protect the unity of Pakistan. They will never allow the country to be disintegrated."

Teacher Abdul Khalek further states, "For the sake of Islam, for the sake of the unity of Pakistan, if necessary, our armed forces will occupy Pakistan a year before. They will run the country under military rule. Therefore, it is seen that the Bengali nationalist teacher Dr. Malek's house is invaded by the marauding force after looting his money and valuables, taking hostage two daughters and his wife who have not returned.

Martyr Anwar Pasha portrayed the massacre at Jaganath Hall, expressing, "The entirety of life seemed paradoxical as he observed the bodies of men and women freshly buried on the premises of Jaganath Hall, with some hands and feet resembling the soil-dust of uprooted tree-children, lifting their heads. How many bodies lie here? And in how many places does such a scene repeat itself?"

At the end of the novel lies the description of the horrific incident on March 25th, within the infernal carnage where those who managed to escape, as Anwar Pasha conveyed in his speech, became a living statement for Bengalis at that time. Leader, at the time, proclaimed, "Bengalis have now learned to die, so there is no power on the earth capable of killing them completely. Those who fear death are the ones who want to escape death."

The sentences concluding the writing in June became truly poignant for Bengalis in the subsequent era. The struggle for survival or the ordeal of living as rebels was an open path for Bengalis at that time. Anwar Pasha was courageous, but survival was not destined for him. He had etched the achievement of life sitting in the city of death in the blood's script in the novel. Hence, the assailants from Pakistan arrived in the form of human beasts.

The dawn for which there was so much suffering, so much hope, so much eager anticipation, had truly arrived for the protagonist of the novel, Anwar Pasha. However, Anwar Pasha could not witness it. He has been killed, but his creation cannot be murdered.

Bangabandhu, Rabindranath, the partition of the country, the mindset of Pakistani rulers, and the conduct of the assailants—all have found their place in his novel. Not only that, but the narrative also delves into the involvement of the Islamist party Jamaat-e-Islami, which was a part of the Al-Badr force. However, their affiliation with the Al-Badr force did not exempt them. Just as Lorca couldn't escape death, neither could Anwar Pasha.

On December 14, the Martyred Intellectuals Day, memories of all martyrs come to our mind. Teachers, intellectuals, artists, journalists, and professionals were among the martyred. Anwar Pasha will be remembered for his significant contribution to this great creation.

Those who were martyred that day, at the hands of the enemy forces and their collaborators, are revered for two reasons. Firstly, they sacrificed their lives for the country. Secondly, they were not ordinary individuals; they stood out through their extraordinary intellect, challenging the atrocities against the people and culture of the country. The aspirations of the Martyred Intellectuals were to liberate the country. This aspiration was universal at that time. They collaborated with various anti-liberation forces within the country, supporting them in various cruel acts, and strategically positioning themselves for the successful execution of the collaborators' plans. However, these demons were not countless in number.

In the deep patriotism of the Bengalis, they had risen like a barricade. Their various conspiracies had failed against the people and culture of the country. Those who have been rehabilitated, supported, and brought back to life by the same force that had tried to destroy them have been tirelessly working to undermine the ideals of independence and the liberation war for a long time. However, their numbers are no longer negligible today.

Today, as intellectuals within the country actively resist internal enemies, this optimism is not baseless. Those intellectuals who became martyrs in December 1971, if the present-day intellectuals, raise their heads high against these enemies, will be offered sincere homage.

The writer is a prominent journalist and incumbent Director General of Press Institute Bangladesh (PIB)

Messenger/Alamin