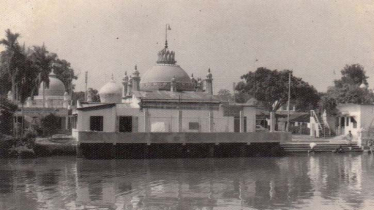

Photo : Messenger

When you speak of Ekushey February, when you recall the sacrifices made on a Falgun day fifty-five years ago, you essentially go through a recapitulation of history as it came to shape history in our part of the world.

You realise that perhaps yours has been the one nation on earth which has had the beautiful spectacle of seeing some of its young give their blood in defence of their language.

Nothing can be more precious than speaking your language, and nothing can be more obscene than discovering the sordid reality of people inhabiting lands far away zooming in on you to tell you cannot any more speak the language you were born to. Or if you have to speak it, you must do so with suitable adjustments and amendments brought into it.

The story of how Muhammad Ali Jinnah attempted to herd the Bangalees into something called Pakistani linguistic uniformity is too well-known and well-remembered to need any repeating. And then there was Khawaja Nazimuddin, the non-Bangalee from East Bengal unwilling to heed the wishes of the people in whose midst he lived, and all too ready to serve the cause of those who thought Urdu could bring the two disparate wings of Pakistan together.

Consider this fantastic thought. If in the 1940s, it was Islam which was to provide a basis for the state of Pakistan, by the early 1950s it was believed by the Muslim League ruling coterie that Urdu would cement that basis. In either instance, the state of Pakistan rested on a weak proposition, on weaker political underpinnings. In the new state, mercifully, it was the culturally homogeneous Bangalees who remained the one body of people who could safely distance themselves from such absurdities.

A clear example of these absurdities we speak of manifested itself early on when Pakistan's ruling classes tried their hands at a recasting of the Bangla language. What better way to do that than through Bangla news broadcasts on Radio Pakistan's Dhaka station? What they thought would be a path to Islamic enlightenment, a clear shaping of Pakistani ideology turned out in the end to be so much philistinism.

In the years that followed, more such examples of crudity would follow, each one of them making it obvious why Pakistan was not destined to last, at least not in its eastern part. If you sit back on this wonderful, soulful morning and remember your history, you will have cause to recall all those peculiarities that were to speed up the process of Pakistan's political disintegration.

If in the 1940s the wholesale programme of the Muslim League was to peddle the notion that a religious community could indeed call itself a nation and so would need a new country for itself, in the 1950s and 1960s the idea behind the working of the military-civilian bureaucratic complex which seized control of Pakistan was to do all it could to slice away at the cultural traditions of its Bangalees and so bring these 'insufficiently Islamic' people into line. And what better way to do that than to humiliate the Bangalees' biggest cultural icon Rabindranath Tagore and send him packing?

It did not matter that in Tagore the Brahmo Samaj was working. He didn't have to be a poet. He was not a Muslim, was he? And so he was evicted, or so the defenders of Pakistan's Islamic ideology thought. If in 1961, when Bangalees enthusiastically observed the centenary of Bard's birth, the military regime of Ayub Khan could not be seen to be doing a bad thing by clamping a ban on such celebrations, in 1964 it entertained no such compulsions, no such diffidence any more. With cheerful backing from Khawaja Shahabuddin (and he was brother to the old Bangalee-allergic Khawaja Nazimuddin) and Abdul Monem Khan, Field Marshal Ayub Khan decreed that the 1913 Nobel literature laureate had to depart from Bangla consciousness. And history.

You note that in the near quarter century, Bangalees spent being part of the Pakistan puzzle, the ruling classes had little to do with strengthening democracy, shaping credible economic policies and, overall, outlining their visions for the future. Every act of theirs was focused on checking the rising spate of Bangalee cultural nationalism.

It was convenient. Any and everything that gave off the whiff of secularism was but a weapon which 'Hindu' India would use in its unending 'conspiracy' to undo Pakistan. By that measure, Tagore was Indian, Nazrul was Muslim and so on and so forth. Willing Bangalee intellectuals, a section of them, went gleefully into the business of promoting a Pakistani culture of the kind that would please the Urdu and Punjabi-speaking elite in West Pakistan.

When that too did not work out to specification, there was the Agartala conspiracy case to fall back on. Nothing would work better than humiliating Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and through him humiliating his people and thereby ensuring the communalistic continuity of the Pakistan state.

It was to ricochet, hard enough to humiliate Ayub and his cabal into scurrying away from power. But before that happened, the bigger humiliation occurred when Ayub Khan welcomed Sheikh Mujibur Rahman at the round table conference in Rawalpindi in February 1969. Bangalee power was clearly in the ascendant.

Think of an autumn day in September 1974. The Bangla language, on that day, was heard across the world when Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman spoke before the General Assembly of the United Nations in New York. It is a day we have remembered, for another quite like it has not happened.

No other Bangladesh head of government has called forth the political integrity to do what the Father of the Nation did in that moment etched in our collective national memory. But let that be. What matters is that twenty-two years after the Pakistani police did all it could to stifle the voice of Bangalee dissent, the Bangla language was being heard in all its melody and resonance in the councils of the world. Only three years previously, an arrogant captain of the Pakistan army had told Anthony Mascarenhas (and that was in 1971) that the military would make sure that the Bangalees stayed a subject race for the coming thirty years.

On the streets of Dhaka, signboards on Bangalee shops cheerfully displayed Urdu letters and phrases. One of the streets was even named 'Tikka Khan Road', to 'honour' the man who had initiated the genocide that would leave three million Bangalees dead and so see Pakistan haemorrhage to its deserved end in Bangladesh.

In early 1974, months before Bangabandhu strode to the rostrum of the UN General Assembly, Bangalee pride went up quite a few notches when Bangladesh's leader and with him his nation back home heard Shonar Bangla played by a band of the Pakistan army at Lahore airport. There was cheerful irony in the air.

The state which had banished Tagore, had tried Mujib for treason, had murdered three million of his people and had seen in the Bangladesh flag all the tell-tale signs of Bangalee treason, was now playing Tagore and displaying that flag on its territory. Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, who thought Allah had saved Pakistan on 25 March 1971, stood at uncomfortable attention beside the man who had been elected leader of Pakistan's majority political party at the 1970 elections and then had become transformed into independent Bangladesh's founding father.

Tikka Khan, he who had had Mujib arrested and flown off to West Pakistan, stood in stiff salute as Amar Shonar Bangla played on. It was a true culmination of the story that had unfolded in February 1952. And this was another February, in 1974. This morning, patriotism is in the air. And, with that, pride. That you have a home of a free state that you speak your language everywhere you go, beyond the frontiers of your country, that you are known as a Bangalee - all of these recreate the old dreams in you. And yet let there be no illusions about where we have faltered in these past many years.

When you hear some of your own Bangalees speak bad Bangla, when they bring in so many English terms and phrases into the language they speak and so mutilate it, you are appalled. Your bureaucrats remain fond of foreign languages. At home, the inanity of Hindi on all those television channels has turned into a ubiquity. Corrupt ministers in well-tailored Western suits feel little embarrassment in haranguing half-clad peasants in your remote villages on the values of hard work.

Elitist education, in the form of so many English medium educational institutions all the way up from schools to universities, makes you wonder what fate awaits the rural child whose dreams of prosperity are regularly undermined by the grinding poverty he and his family plod through.

Of course, patriotism is in the air. But when it comes on hollow wings, when you are inclined to ignore the realities you stumble into day after day, all life, every sense of values, loses meaning.

Do you realise that Jabbar, Barkat, Rafiq and all those other bright young men were our earliest martyrs? And then came Asad, Zoha, Zahurul Haq and Motiur? The war of 1971 made three million martyrs of us. Dhirendranath Dutta was murdered on a rain-soaked April street in Comilla. In 1975, we lost Bangabandhu, Tajuddin Ahmed, Syed Nazrul Islam, AHM Quamruzzaman and Mansoor Ali. Khaled Musharraf was murdered by men uncomfortable with the truth.

All this blood could not have gone in vain. We rise and stumble and fall, only to rise again. That is the promise we can renew to ourselves this morning. Let the memory sweep across the historical train of sacrifice, from 1952 to 1975. That is how we will remember. Memory is what prevents us from forgetting.

Syed Badrul Ahsan is a senior journalist, columnist and political analyst. He could be reached at:

Messenger/Sajib