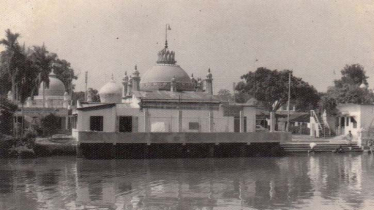

Photo : Messenger

Shipbreaking means, what visually comes to one’s mind, breaking old ships into pieces for disposal or recycling. One of the primary areas in the world that specialises in shipbreaking is Bangladesh.

Ship breaking industry started its cruel journey in 1960, when most environmentalists, NGOs and media had no clue to understand the fathom of the brutal impact on the environment, human health, agriculture and the burden on healthcare management.

In addition to its human impact, the shipbreaking industry in Chattogram is destroying environmental ecosystems in Sitakunda Beach.

The ships coming to Bangladesh to berth at the tidal mudflat coast of Chattogram to die. The ship scrapping industry is a dirty and dangerous economic activity amid poor transparency and inadequate monitoring systems by the authorities.

Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCB), engine oil, spent fuel, and asbestos concentrations at ship recycling yards on the beaches of Chattogram are at alarming levels. The industry in Bangladesh is highly dangerous and unregulated.

The monitoring of the shipbreaking industry by non-government agencies (NGOs) and regulatory agencies (Department of Environment) lacks inclusive training, expertise and equipment to monitor the dirty business.

The NGO's only tools they have are non-comprehensive environmental laws, international conventions and guidelines, which the shipbreaking owners dare to flout. The punishment and punitive actions against the defaulters are very weak and the process is delayed due to bureaucracy and the judiciary is corrupt.

Shipbreaking in Bangladesh has exponentially grown over the decades along the coasts of Chattogram. More than 50% of the gross tonnage dismantled globally is handled on the beach of Chattogram, a “toxic hotspot”.

The shipbreaking yards in Bangladesh are located just outside the major port city of Chattogram. They stretch along the coastline of the Sitakundu area for approximately 15 km.

The country cannot properly manage the extremely dangerous toxic materials that are generated from the dismantling of end-of-life vessels on the beach, outside a contained zone.

At the yards, toxic exposure is accepted at a price for domestic economic development and employment, while allowing ship owners from the Global North to exploit weak laws and externalise costs.

Most vessels are imported to Bangladesh with false documents which claim the vessel is asbestos-free. The powerful shipbreaking industry, which generates more than half of Bangladesh’s raw steel supply, has had a devastating impact on workers’ lives and the environment, and European shipowners are frequently shamed for sending their vessels to Bangladesh for demolition with no respite.

Magsaysay Award recipient and environmental lawyer Syed Rizwana Hasan, also Executive Director of the Bangladesh Environmental Lawyers Association (BELA), said: “European ship owners send their end-of-life tonnage to the beaching yards because that is where they can make the highest profit.

They ought to know that their vessels contain numerous toxic materials, including asbestos, and that the conditions at the shipbreaking yards in Bangladesh are appalling. This exploitation of poor coastal communities is for the financial benefit of an already wealthy shipping industry."

The ship-breaking industry in Chattogram remains extremely dangerous for workers and the environment. The top ship-recycling country in the world has failed to regulate the clandestine business effectively, for which frequent death, injury and pollution continue to be in the headlines.

The story says that shipbreaking started in Bangladesh in 1960 when a cyclone coupled with the tidal surge in the Bay of Bengal washed a Greek ship MD Alpine onto the shore and stuck in the mud flat for months. After the damaged vessel was declared abandoned, it took more than a year to shred, with no knowledge of the dangers waiting for the workers and the environment.

Bangladesh is a top destination for scrapping ships. Since 2020, approximately 20,000 Bangladeshi workers have ripped apart more than 520 ships, far more tonnage than in any other country.

The World Bank has estimated that between 2010 and 2030, Bangladesh will have imported 79,000 tons of asbestos; 240,000 tons of PCBs and 69,200 tons of toxic paints that originate from end-of-life ships.

Since the Chattogram shipbreaking yards remain void of storage and treatment facilities for hazardous wastes, these toxins are simply dumped or re-sold on the second-hand market and cause further harm to surrounding communities.

The industry directly employs 50,000 people and another 100,000 indirectly and provides around 80 per cent of the country’s steel.

End-of-life ships are considered toxic waste under the Basel Convention because they are full of toxic materials: asbestos is used as insulation; heavy metals like cadmium, lead, and chromium are in paints and coatings for batteries, motors, generators, and cables; mercury is in thermometers, electrical switches, lights, and often in vessels that have operated in the oil and gas extraction sector; oils, fuel, harmful bacteria, and toxic sludge are found in bilge water, sewage, and ballast water; PCBs are in cables.

Most ships headed for the beaches in South Asia were built decades before international rules banned the use of asbestos in shipbuilding in 2011.

Every day, the huge cargo ships are taken apart by hand by unskilled labourers recruited from poverty-stricken villages in the north of the country. The labourers do not comply with work safety guidelines, which are not strictly imposed. Nor do labour laws are enforced.

Bangladesh is a signatory of the Basel Convention, which is supposed to stop hazardous waste, especially asbestos, from being dumped in developing countries.

In 2009, the Supreme Court ruled that, in keeping with this convention, ships should be cleared of their hazardous materials before they are imported for demolition in Bangladesh.

Two years later, the Supreme Court ordered a ban on beaching giant ships containing asbestos to the coast of the Bay of Bengal.

Most of the end-of-life vessels are imported with fake certificates claiming that they are free of hazardous materials. As a consequence, toxins are not properly detected and safely removed.

The environmental laws and guidelines are flouted by the shipbreaking owners, who have political clouts, supervisors and private buyers for illegal markets who also work as the yard’s henchmen.

NGO Shipbreaking Platform’s Bangladesh Coordinator, Muhammed Ali Shahin and also the programme coordinator for an NGO, Young Power in Social Action (YPSA), said there is an international guideline to remove asbestos from the ships. "Asbestos poisoning can be curbed by dismantling ships in green and environment-friendly shipyards that follow the guideline," he said.

Award-winning environmental lawyer Rizwana Hasan said, "The ships that are older than 20 years contain asbestos in the engine room, boiler, and many other places where it requires heat and fire resistance. As per international guidelines, experts should remove asbestos and bury it underground.

The president of the Bangladesh Ship Breakers and Recyclers Association, Abu Taher, is in denial mode of large-scale asbestos poisoning among ship-breaking workers. There is no asbestos victim in the industry, as the ships built after 2000 do not carry any asbestos.

Asbestos is not only mismanaged at the shipbreaking yards but also re-sold in the second-hand market in Bangladesh. Hundreds of shops and two and three-storied markets have sprung up to sell merchandise retrieved from the ships on both sides of the Chattogram-Dhaka highway.

A 90-page report, “Trading Lives for Profit: How the Shipping Industry Circumvents Regulations to Scrap Toxic Ships on Bangladesh’s Beaches,” released by New York-based Human Rights Watch (HRW) and the Brussels-based NGO Shipbreaking Platform, finds that Bangladeshi shipbreaking yards often take shortcuts on safety measures, dump toxic waste directly onto the beach and the surrounding environment, and deny workers living wages, rest, or compensation in case of injuries.

Shipbreaking in Bangladesh is strongly criticised by both international and local NGOs due to its dirty and dangerous practices. Concerns include abysmal working conditions, fatal accidents, exploitation of child workers, and severe pollution of the marine environment, as well as the dumping of hazardous wastes.

In 2009, following litigation by NGO Shipbreaking Platform member organisation BELA, a landmark decision by the Bangladesh Supreme Court ordered the closure of all shipbreaking yards in Chattogram as none held the necessary environmental clearances to operate. After only two months of closure, the yards re-opened with incomplete authorisations in hand and no change in practice.

In 2016, the Supreme Court issued a contempt rule against both the authorities and shipbreaking yard owners for continued breaches of the 2009 order.

After a decade, the government was forced by the Supreme Court to introduce rules to protect workers. An investigation from an independent newspaper in Bangladesh, The Daily Star and Finance Uncovered, suggests that a major part of the country’s regulatory system is a sham.

The writer is Deputy Editor, The Daily Messenger. He can be reached at [email protected]

Messenger/Fameema