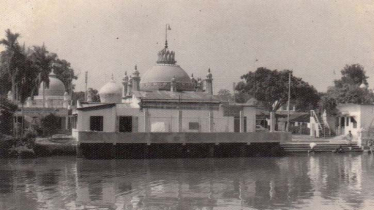

Photo : Messenger

Bangladesh stands among the most densely populated countries of the world sans a few city states thriving on islands. Although a delta with alluvial soil, all its citizens are not as lucky as their counterparts in the tiny islands of business hotspots across the world. The land-man ratio here is one of the lowest in the world; 0.047 in 2021 (FAO). With growing population, urbanization, industrialization, land erosion, acquisition of arable land for non-agricultural purposes, adversities of the smallholders and successive global and local shocks are exacerbating the overall landholding ratio, raising the landlessness to an alarming proportion. But the job-creation in the country for the unskilled and educated labor force is not in keeping with the demand. So, the ultimate destinations of the landless and jobless people are the cities, towns and industrial enclaves for seeking employment. This creates unbearable pressure on the civic amenities in the urban and industrial hubs.

Springing of slums for huddling residential purposes and occupying thoroughfares for business opportunities by these fortune seekers of the rural areas are almost seen everywhere in this metropolis to the discomforts of the well-off citizens. Our city fathers, themselves in most cases belonging to the upper echelon, are equally armed with legal and operational capabilities to uproot them from their makeshift huts and floating kiosks, to the comforts of the class they belong to, but only for the time being. As soon as the evictors leave the places of reoccupation, the process of dispossession starts again. This is a perennial Tom and Jerry game seen from time immemorial. The movie Shree 420 made in the 1950’s by Raj Kapur depicts the precarious conditions of these floating people in the urban areas vividly. In this connection, comes the question of illegal and forcible use of public properties for redressal on the one hand, while on the other hand, the social, ethical, economic, humane and constitutional obligations ooze out to vie with the former conundrum.

After the World War 2, the world community realised the need for protection of human rights both nationally and globally. So, they adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) in 1948. Later in 1966, another two sets of documents, namely, International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) were put in place under the auspices of the UN. When Bangladesh adopted her constitution in 1972, these two sets of rights got recognized: as part of the fundamental principle of state policy in Part 2 and as judicially enforceable fundamental rights in Part 3 of the constitution. The objective of this constitution was to establish an egalitarian society where human rights and the principles of equality will rule the roost. For example, article 14 of the Constitution reads, “It shall be a fundamental responsibility of the State to emancipate the toiling masses, the peasants and workers and backward sections of the people from all forms of exploitation.” Moreover, attainment of basic necessities of life, including food, clothing, shelter, education and medical care for all its citizens has been made one of the fundamental responsibilities of the state. And the citizen’s right to work, that is, the guaranteed employment at a reasonable wage having regard to the quantity and quality of work has been categorically enunciated in the supreme law of the land. Again, Bangladesh is a party to different international human rights covenants which stipulates that it is the duty of the state to uphold the human rights of its citizens.

If anyone goes through these safeguards of the citizens, given in the constitution or international covenants, one can easily come to the conclusion that anybody cannot go for arbitrary eviction of the squatters without making adequate provisions for their rehabilitation. But in a country where ‘might is right’ principle rules supreme, who cares for the rule of law involving the protection of rights and improvement of lives of the downtrodden. The eviction of the Gopibag T.T. Para Sweeper colony, inhabited by sweepers of Horizon and Telugu origin is a case in point. This community once used to work under the railway authority in the areas adjacent to Phulbaria old railway station. They had been moved to T.T. Para in Kamlapur 42 years ago to make space to construct Nagar Bhaban. This time, it is the railway line connecting Kamalapur to Jeshore which is the cause of their uprooting. A victim of this community lamented, ‘we have been living in Bangladesh for about 200 years, yet we have not a house to live in.’ This is really inhuman and heartrending, calling for urgent redress.

But things do not follow the same tenor everywhere. One report has it that in Sylhet, around 1.5 years back, about 100 illegal structures had been demolished in the areas of Pathantuli and Madina Market by the City Corporation. But the unlawful structure of Rahat Complex still stands out, defying all legal barriers. It is alleged that the building belongs to one of the councilors (Prothom Alo, 28 February, 2024). Another interesting report is about a civil servant, who went on retirement in June in 2017 with the usual PRL (Post Retirement Leave) of one year (Prothom Alo, 27 February, 2024). The civil servant, an additional secretary, once serving as Director, Directorate of Govt. Accommodation prior to his retirement, has allegedly been living unlawfully in the house after retirement for about five years. Rental dues receivable from him now reportedly stands at Tk. 30 lac.The Public Works Department, finding no other alternative to dislodge him from the house, has resorted to eviction with magistrate and supportive staff. But on the halfway mark, they had to leave the spot without finishing their task as the occupant showed them an instruction of the concerned minister that on compassionate ground his staying in the house may be extended up to impending Eid Ul Fitr.

The illegal occupant claims that he is a freedom fighter and he has no house in Dhaka. So, on completion of PRL in 2018, he applied to the PMO (Prime Minister’s Office) for granting permission to overstay there for a period of two years. According to his version, he was granted that perquisite. At the conclusion of that term in 2020, he, as a valiant Freedom Fighter (FF), furnished another prayer for the house, this time not for a term, but forever. But the PMO did not respond till date. So, this prompted the Public Works Directorate to make adequate arrangements for eviction at their own expenses. The eviction party comprised as many as 13 police constables and 4 ansars, 10 laborers, some officers of the Directorate led by a magistrate.

This incident brings certain interesting points to the fore which need to be solved sooner than later. Freedom Fighters are the golden sons of the soil; their contribution to the emergence of the very nation can hardly be overemphasized. Definitely they deserve recognition as well as material privileges for honorable living, if need be. Nobody is likely to dispute that. But there should be a set of criteria and principles guiding these operations, so that nobody remains in confusion. If the FF in question is given the house for good, others with similar or better credentials will follow suit; in that event, the government has to be prepared with adequate resources and arrangements. Again, if it decides in the negative, it should be intimated forthwith to avoid any misunderstanding and operational complexities. So, confusion crept in and resources and time were allowed to get squandered.

Everywhere in the world, eviction is done at the owner's expenses (meaning at the delinquent’s expenses). If anyone visits the USA, one is likely to come across a distinct plaque quite often in the city reminding a message, ‘Unauthorised cars will be towed away at the owners’ expenses.’ In our country, appropriate eviction law is there, but in most cases, eviction is done at the government’s expenses. In the case cited above, all expenditures are incurred and time consumed on the part of the government and its officials. This stands in the way of proper usages of government resources, smooth functioning of the machineries and good governance the government at present is insisting on.

Whatever unpalatable it may sound, the fact remains that it is the marginalised segment of the society that fall victim to exploitation and discrimination, be it by criminals or authorities and influential and vested quarters go scot-free. So, it is high time the authorities revisited their approach towards resettlement of the victims and ensured that everybody is equal and some are not more equal than others.

The writer is the former Director General of the Directorate of Foods and is a columnist. He could be reached at [email protected].

Messenger/Fameema