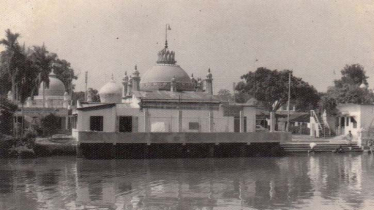

Photo: Messenger

Bangladesh, a nation perched on the Bay of Bengal, is no stranger to natural disasters. Each year, the country faces the wrath of cyclones, floods, tornadoes, and tidal bores, with devastating consequences. The most recent catastrophe, Cyclone Remal, struck both Bangladesh and India, causing widespread havoc along the coastal belt.

One of the most significant casualties of Cyclone Remal was the Sundarbans, a vast mangrove forest that has long served as a natural barrier against such disasters.

Known as Bangladesh’s silent sentinel, the Sundarbans, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, has historically protected the coastline from the full impact of storms. According to several newspapers, Remal’s 36-hour onslaught left a trail of destruction, including the tragic loss of at least 130 deer and other wildlife, hinting at the broader impact on the ecosystem, including vulnerable tiger cubs swept away by the surge.

The story of Cyclone Remal is not an isolated incident. There has been a troubling increase in both the frequency and severity of cyclones hitting the Bangladeshi coast. Historical records show that these storms, such as Sidr and Aila, have caused lasting damage to the landscape and the people who live there.

Yet, through all this, the Sundarbans have remained a critical line of defence, reducing the impact of these natural disasters on coastal communities. The Sundarbans is a marvel of biodiversity, covering over 10,000 square kilometers and providing a sanctuary for countless species, many of which are endangered, according to government data. This dense mangrove forest offers more than just protection from storms; it supports a range of ecosystem services crucial for the environment and human livelihoods.

These include carbon sequestration, flood regulation, and providing resources for local communities who depend on fishing, honey collection, and other activities. It also acts as a protective barrier against storms, cyclones, tidal surges, and seawater intrusion.

Bangladesh, situated within the Bay of Bengal’s embrace, is constantly at the mercy of nature’s whims. The coastal areas are particularly vulnerable to cyclones and tidal surges, which disrupt life and cause extensive damage. Cyclones typically strike before the monsoon season, bringing a pattern of destruction that repeats with alarming regularity. The geography of the Northern Bay of Bengal, with its triangular shape and deep continental shelf, makes the region especially prone to these storms.

Experts have long warned that climate change is exacerbating the frequency and intensity of cyclones in Bangladesh.

Recent years have confirmed these fears, as the country experiences more frequent and severe storms.

In this context, the Sundarbans’ role becomes even more crucial. Mangrove forests, like those in the Sundarbans, act as natural defenses against cyclones and tidal surges, absorbing much of the energy from these storms and reducing their impact on inland areas.

Mangroves are often described as providers of indispensable ecological services. They form natural barriers that protect coastal communities by diminishing the force of storms and tidal surges. These dense forests mitigate the risks associated with these natural disasters, offering a buffer of security for those living in vulnerable areas. Despite their importance, the economic value of mangroves in protecting against storms and tidal surges is not fully appreciated.

In 2017, a pivotal report by the World Bank Group highlighted the critical importance of mangrove forests in protecting Bangladesh from the devastating impacts of cyclones and tidal surges.

This comprehensive study revealed that the diverse species of mangroves, their dense canopy, and their robust structure are essential in mitigating the effects of nature’s fury. The findings showed that mangrove forests, which vary in width from a few meters to several kilometres, have the ability to reduce the height of tidal surges by four to sixteen and a half centimeters. Additionally, mangrove areas, rich with bines and keora trees or Mangrove apple (Sonneratia apetala), spanning widths of fifty to one hundred meters, can significantly slow down water flows by an impressive twenty-nine to ninety-two percent.

The report also provided valuable advice on the strategic planting of mangrove saplings, particularly on newly formed islands and char lands. It emphasized the necessity of embankments and the importance of reinforcing these barriers with mangrove vegetation. Despite these wise recommendations, the Sundarbans, a vast and biodiverse mangrove forest, faces severe threats.

Once a thriving ecosystem, the Sundarbans is now at risk due to ecological imbalances.

The once-vibrant branches of the Padma River, such as Gorai, Mathabhanga, Arial Khan, Madhumati, Kabadak, Chitra, Ichhamati, and Bhairab, have dried up; their waters diverted by human activities.

The Farakka Barrage has disrupted the natural flow of these rivers, endangering the Sundarbans and causing the disappearance of crucial tree species like the sundari (Heritiera littoralis).

However, illegal hunting, timber extraction, and agricultural encroachment threaten the area despite legal protections. Additionally, storms, cyclones, and tidal surges, which can reach up to 7.5 meters high, pose increasing threats due to climate change.

However, as the threats of climate change grow, so too does the need for robust conservation efforts. Preserving the Sundarbans is not just about protecting a forest; it is about safeguarding the future of Bangladesh’s coastal communities against the increasing severity of natural disasters. The resilience of this mangrove forest is a testament to nature’s ability to protect and sustain life, even in the face of relentless adversity.

These alarming issues call for immediate and decisive action. Strict regulations must be enforced to prevent polluting industries from operating within a ten-kilometer radius of the Sundarbans, and existing polluters must relocate. Vigilance and stringent legal measures are essential to protect these sacred lands. UNESCO’s recommendations for conservation should be implemented through thorough Environmental Impact Assessments.

On December 9, 2014, an oil tanker collided with a cargo ship on the Shela River in the Sundarbans, releasing nearly half of its 94,500 gallons of furnace oil into the river.

This spill spread over more than 35 miles of the area’s delicate rivers and canals, threatening the rich biodiversity of the Sundarbans. The oil spill endangers local wildlife and jeopardises the livelihoods of millions of nearby residents. To protect this vital ecosystem, waterways like the Shela River should be permanently closed to such traffic, and strict accountability should be enforced for those violating maritime laws.

In the face of these threats, public awareness and collective action are crucial. Sundarbans Day, celebrated annually on February 14th, serves as a powerful reminder of the need to preserve this unique ecosystem. This day of commemoration is a call to protect the Sundarbans and ensure its sustainability for future generations. It underscores the importance of foresight and the need to act responsibly as guardians of this precious natural heritage.

Stringent regulations are necessary to protect the Sundarbans from encroachment and pollution. Vigilant enforcement of conservation measures is vital to safeguard this biodiversity hotspot.

As stewards of this invaluable legacy, we must take responsibility for protecting and cherishing the Sundarbans for generations to come.

The writer is a journalist who has worked at several reputable national English dailies and international news platforms. Currently, he is employed at the national English daily, The Daily Messenger.

Messenger/Fameema