Photo: Courtesy

Lassa fever is an acute viral hemorrhagic illness caused by the Lassa virus, a member of the Arenaviridae family. It is endemic in parts of West Africa, including Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Guinea, where it poses a significant public health challenge. This virus was first discovered in Nigeria in 1969.

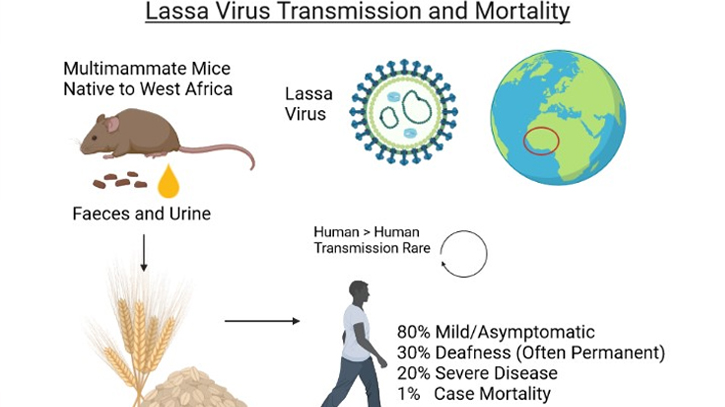

Transmission

Reservoir of Lassa virus is a rodent of the genus Mastomys, known as the Multimammate rat. The virus is presented in urine and feces of infected rats. Primary human infection occurs by food or household items contaminated by infected rats urine and feces and direct contact while handling the rats. Secondary human infection occurs by human to human transmission with blood, secretion, organ and other body fluid of infected person.

Clinical Manifestation

The incubation period of Lassa fever ranges from 5 to 21 days. Approximately 80% of infections are mild or asymptomatic, making diagnosis difficult. However, the remaining 20% of cases can progress to severe disease. Early symptoms are non-specific and include fever, general weakness, and malaise. As the disease progresses, patients may experience headache, sore throat, muscle pain, chest pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, cough, and abdominal pain.

In severe cases, patients can develop hemorrhagic symptoms, facial swelling, fluid in the lung cavity, bleeding from the mouth, nose, vagina, or gastrointestinal tract, and low blood pressure. Neurological problems, including hearing loss, tremors, and encephalitis, can also occur. Approximately 15%-20% of hospitalized patients with Lassa fever die from the illness. However, the overall case fatality rate is lower, around 1%.

Moreover, it is more severe in pregnant women and their fetuses. The fetal death is more than 85%. There is also increased maternal mortality rate in third trimester more than 30%. Infant (up to 2 years old) cases presented with Swollen Baby Syndrome associated with high case fatality rate.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing Lassa fever can be challenging due to its non-specific symptoms, which overlap with many other febrile illnesses common in West Africa, such as malaria and typhoid fever. So, patient history is essential and should include exposure to rodent and/or area/village where Lassa virus is endemic and/or contact with infected of Lassa virus.

Laboratory testing is essential for confirmation. The gold standard for diagnosis is the detection of Lassa virus RNA by Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR). Other diagnostic methods include Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) to detect Lassa virus antibodies (IgM and IgG) and antigen detection tests.

Treatment

Early supportive care with rehydration and symptomatic treatment improves survival. The antiviral drug ribavirin has shown efficacy in treating Lassa fever, especially when administered early in the course of the disease. However, its availability is limited, and its use is associated with potential side effects. Moreover we should administered painkiller, antiemetic for vomiting and anxiolytic for agitation.

Other treatments are mainly supportive and include managing fluid and electrolyte balance, oxygenation, and treating any secondary infections. In severe cases, intensive care may be necessary.

Prevention & Control

Preventing Lassa fever relies heavily on community and public health measures aimed at reducing rodent populations and limiting human-rodent contact. Key strategies include:

1. Rodent Control: Promoting good hygiene and sanitation practices to discourage rodents from entering homes. This includes storing food in rodent-proof containers, disposing of garbage far from homes, and maintaining clean living environments.

2. Education and Awareness: Educating communities about the risks of Lassa fever and measures to prevent infection. Public health campaigns can help inform people about the importance of avoiding contact with rodents and practicing safe food storage and preparation.

3. Protecting Healthcare Workers: Ensuring that healthcare workers adhere to standard infection control practices, including the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) and safe injection practices. Isolation of suspected Lassa fever patients can help prevent nosocomial transmission.

4. Surveillance and Reporting: Strengthening disease surveillance systems to ensure timely detection and reporting of Lassa fever cases. This helps in initiating prompt public health responses to contain outbreaks.

5. Research and Development: Ongoing research is crucial to better understand Lassa fever and to develop effective vaccines and treatments. Currently, there is no licensed vaccine for Lassa fever, but several candidates are in various stages of development.

Epidemiology

Lassa fever was first identified the town of Lassa in Borno State, Nigeria. It is estimated that 100,000 to 300,000 infections occur annually, with approximately 5,000 deaths. The true incidence is likely higher due to underreporting and misdiagnosis. The disease predominantly affects rural areas where the multimammate rat is common. These rodents are the primary reservoir for the Lassa virus, shedding the virus in their urine and feces, which contaminates food and household items.

Conclusion

Lassa fever is a complex disease with significant public health implications in West Africa. Understanding its epidemiology, transmission, clinical manifestations, and available treatment options is crucial for effective management and control. Preventive measures, including rodent control, community education, and protecting healthcare workers, are vital in reducing the incidence of Lassa fever. With ongoing research and international cooperation, there is hope for improved outcomes and the eventual control of this deadly disease.

Messenger/Disha