Photo : Messenger

Bangladesh finds itself at a pivotal moment, where the increasing prevalence of mob lynchings threatens both the spirit of the July mass uprising and the reformist initiatives of the interim government. The surge in mob violence signals a growing breakdown of law and order as institutions weaken and public frustration mounts. This rise in vigilante justice, particularly during political transitions, has revealed deep flaws in the country’s democratic and legal structures. What began as a movement for reform has tragically spiraled into violence and mob retaliation, undermining the fundamental principles of justice and human rights.

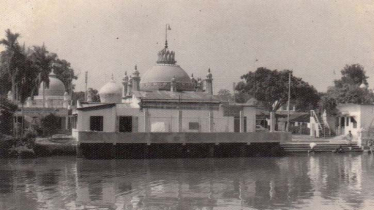

The brutal lynchings of former Bangladesh Chhatra League leaders at Jahangirnagar and Rajshahi universities, alongside the murder of an alleged thief at Dhaka University, are stark reminders of the lawlessness that has emerged. Earlier this month, in Khulna, a Hindu teenager was violently attacked by a mob over accusations of blasphemy, while several mazars (shrines) across the country have been vandalized. These incidents are not isolated but part of a broader pattern of mob violence, spurred by mistrust in the state’s legal system. Mobs have taken on the role of judge, jury, and executioner, bypassing due process and further eroding the rule of law.

Sociologically, this rise in mob violence can be understood through Emile Durkheim’s concept of anomie, a state where social norms disintegrate, and individuals feel disconnected from society. In Bangladesh’s current state of upheaval, public trust in state institutions has diminished, and the failure of justice systems has created fertile ground for mobs to take control. Frustrated by the absence of legal recourse, groups have resorted to violent retribution, believing it to be the only way to restore order and community cohesion. This paradox—seeking justice while destroying the mechanisms that uphold it—threatens the long-term stability of Bangladesh’s democracy.

The consequences of mob lynching go far beyond the immediate victims. It undermines the justice system, creates an atmosphere of fear, and delegitimises the state. In this post-uprising period, where there is a strong desire for reform, mob lynching poses a dangerous obstacle. Without swift and decisive action, Bangladesh risks descending further into chaos, undoing the very progress that the uprising aimed to achieve.

To combat this growing menace, the interim government, led by Professor Muhammad Younus, must prioritise the restoration of law and order. A multifaceted approach is necessary. First, the justice system must be strengthened, ensuring that courts and law enforcement agencies can process cases quickly and fairly. Delays in justice or perceived biases only fuel mob violence, as people lose faith in formal legal avenues. Furthermore, a nationwide campaign of public awareness and education is crucial. Schools, media outlets, and community leaders must work together to inform the public about the dangers of mob justice and the importance of due process.

Equally important is the utilisation of social media platforms, which have become breeding grounds for misinformation. False rumours can spread rapidly, inciting mob action before the truth is even verified. Social media users must be aware while putting any content or opinions in their accounts, with careful oversight and fact-checking needed to prevent the unchecked circulation of rumors. Law enforcement agencies and community leaders also need to be vigilant in areas prone to unrest, ensuring that potential mobs are dispersed before violence escalates.

Post-uprising Bangladesh must also focus on community reconciliation. The scars left by division and mistrust cannot heal overnight, but dialogue-based reconciliation programs can help to address grievances without resorting to violence. These efforts must be community-driven, ensuring that all voices are heard and that justice is seen to be fair and equitable.

Eradicating mob lynching is not solely the responsibility of the government; it requires a collective commitment from society as a whole. Political leaders, civil society organisations, and ordinary citizens must unite to reaffirm their commitment to the rule of law. The energy that fueled the July uprising should now be channeled towards constructive change rather than destructive violence. Only by doing so can Bangladesh prevent the recurrence of mob lynching and strengthen its democracy, ensuring that justice is available to all, not just those who wield the power of the mob.

The path forward will undoubtedly be challenging, but with concerted effort, the rule of law can be restored, and the specter of mob violence can be consigned to the past. It is only then that Bangladesh can build a society where justice is governed by fairness, equality, and human dignity, not by the fury of the crowd.

The writer is experienced in development research, with extensive insights and skills in data analysis.

Messenger/Disha