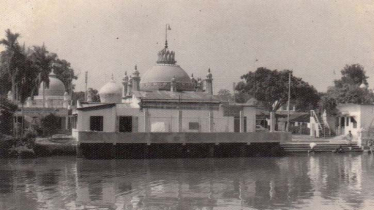

Photo: Collected.

Abdur Gafur, an 85-year-old fisherman from the Munshiganj range of the Sundarbans, has weathered more storms than most can imagine. In 2007, Cyclone Sidr robbed him of 13 family members. Now, it’s just him and his wife, navigating life against the odds, sustained by their unyielding connection to the sea.

When I met him, a three-month ban prevented fishermen from entering the Sundarbans.

Asked why he remains steadfast in his profession despite such hardships, Gafur said, “I have lived as a fisherman and will continue to do so, even if I fail to ensure two square meals every day. Despite losing 13 loved, I still chose to stay by the sea because this is my home.”

Gafur’s resilience reflects the spirit of the entire fishing community in Shyamnagar’s “Jele Para.” These men and women depend heavily on the Sundarbans for their livelihoods, yet they face an uphill battle against climate change, natural disasters, and restrictive government policies.

The double-edged sword of conservation

Government policies aimed at conserving the Sundarbans often leave local communities in dire straits. Between June and August every year, a ban restricts access to the forest and the sea to allow fish populations to reproduce. While crucial for biodiversity, this policy leads to sufferings for around 50,000 people in Satkhira alone who rely on fishing, honey collection, and wood gathering, according to The Business Standard report published this year.

Unable to pursue their usual livelihoods, many fishermen resort to unsustainable practices.

A common alternative during the ban is the illegal hunting of shrimp and crab minnows, which fetch Tk 1,000 for every 100 minnows. While this provides temporary relief, it undermines the very purpose of the fishing ban by disrupting aquatic ecosystems.

Gaps in government support

The fisheries department provides a 56 kilogrammes of rise as subsidy to fishermen affected by the ban, but accessing this aid is fraught with obstacles. To begin with, fishers must hold a “Fishermen Card,” which requires costly registration—an unaffordable burden for many who live hand-to-mouth. This loophole leaves most without support, forcing them into harmful practices or migration.

Some migrate to work as labourers in brick kilns or on farmlands, while others leave permanently for cities like Dhaka. Those who leave seldom return, draining the region of its traditional fishing expertise.

The vicious cycle of poverty and environmental harm

Erratic weather patterns, over-exploitation of resources, and indiscriminate practices like minnow hunting, are creating a vicious cycle. Fishermen report dwindling fish stocks in open waters, a consequence of both natural and human-induced factors.

Meanwhile, illegal shrimp farming and forest exploitation have exacerbated salinity levels, further jeopardising the Sundarbans’ delicate ecosystem.

A call for sustainable solutions

A call for sustainable solutions

Despite a noteworthy effort, the fisher community in Munshiganj are faced with challenges which can only be solved via sustainable alternatives. To break this cycle, stakeholders must work together to introduce sustainable livelihood options tailored to the region. Policies must also be inclusive, addressing the needs of the local community without contradicting conservation goals.

By adopting a holistic approach, it’s possible to ease the struggles of fishermen like Abdur Gafur, who fight daily battles against poverty and the cascading effects of climate change. With the right support, they can preserve their way of life while protecting the Sundarbans for generations to come.

The writer is an intern at CAPRES, ICCCAD

Messenger/EHM