A strong and prosperous middle class is crucial for any successful economy and cohesive society. The middle class sustains consumption, it drives much of the investment in education, health and housing and it plays a key role in supporting social protection systems through its tax contributions. Societies with a strong middle class have lower crime rates, they enjoy higher levels of trust and life satisfaction, as well as greater political stability and good governance.

However, current findings reveal that the top 10% in the income distribution holds almost half of the total wealth, while the bottom 40% accounts for only 3%. It has also been prevailed that economic insecurity concerns a large group of the population: more than one in three people are economically vulnerable, meaning they lack the liquid financial assets needed to maintain a living standard at the poverty level for at least three months.

The Squeezed Middle Class provides an in-depth focus on the current situation of the middle class as an economic and social group. In doing so, it documents the pressures and growing risks building up on this group. Indeed, over the past 30 years, middle-income households have experienced dismal income growth or even stagnation in some countries. This has fueled perceptions that the current socio-economic system is unfair and that the middle class has not benefited from economic growth in proportion to its contribution. Furthermore, the cost of living has become increasingly expensive for the middle class, as the cost of core services and goods such as housing have risen faster than income. Traditional middle-class opportunities for social mobility have also weakened aslabourmarket prospects become increasingly uncertain, one in six middle-income workers are in jobs that are at high risk of automation. Uncertain of their own prospects, the middle class are also concerned about those of their children; the current generation is one of the most educated, and yet has lower chances of achieving the same standard of living as its parents.

Bangladesh's middle class has been facing a number of challenges, including a cost of living crisis, job loss, and the other calamities. Cost of living crisis- The cost of living has increased significantly, while wages have remained stagnant. This has made it difficult for the middle class to make ends meet. Job loss: Many people lost their jobs during the pandemic, Salary and allowance issues: Many people who didn't lose their jobs are not getting their salaries and allowances regularly. Poverty: The pandemic has led to a net increase in poverty in the country. Commodity inflation: The prices of daily commodities have increased uncontrollably.

The middle class has been forced to cut back on their spending on recreation, transportation, medication, health, education, and lifestyle. The government can help the middle class by putting in place policies that promote upward social mobility and provide safety nets. These policies could include: Quality education, Safety nets to protect vulnerable segments when facing life risks.

Ensuring high quality of publicly provided services.

This phenomenon the result of more than two decades of nearly continuous fast-paced global economic growth has been good not only for economies but also for governance. After all, history suggests that a large and secure middle class is a solid foundation on which to build and sustain an effective, democratic state. Middle classes not only have the wherewithal to finance vital services such as roads and public education through taxes; they also demand regulations, the fair enforcement of contracts, and the rule of law more generally public goods that create a level social and economic playing field on which all can prosper.

The birth of new middle classes all over the world therefore qualifies as a conquest of capitalism and globalization. But it is a fragile victory. For the world now faces a period of prolonged slow growth. That is bad news, not only because it could halt the impressive declines in poverty but also because it could set back hopes for better governance and fair-minded economic policy across the developing world, harming both middle classes and the far larger populations of poorer people in the developing world who are the chief victims of weak or abusive régimes. The rich world could lose out, too, since improvements in governance allow poor countries to collaborate with the international community in managing the risks posed by pandemics, terrorist groups, climate change, waves of political refugees, and other regional and global problems. Governments in the developing world and in rich countries alike would do well to nurture and protect the legitimate interests of the new middle classes.

No, there is no single "standard" percentage of middle-class families in a country as the definition of "middle class" varies significantly depending on the country's economic situation, making comparisons difficult; however, according to data from the Asian Development Bank, the global average for middle-class population tends to be around 72.5% in developing countries, while developed countries often have a much higher percentage considered middle class. Key points to remember, no universal definition what constitutes "middle class" differs based on factors like cost of living, income levels, and social norms within each country. Income-based calculations, most commonly, middle class is determined by a range of income levels, with different thresholds for different countries. Regional variations, even within a single country, the middle class percentage can vary significantly between urban and rural areas.

The middle class in Bangladesh is estimated to be between 22% and 34% of the population, depending on the definition used. The middle class is expected to grow in the coming years. Asian Development Bank (ADB) defines the middle class as people who earn between $2 and $20 per day, Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) defines the middle class as people who earn between Tk40,000 and 80,000, Different expert of Bangladesh defines the middle class as people who earn between $2 and $3 per day. Projected growth of the middle class: 2025-The middle class may make up 25% of the population, or around 44 million people, 2030-The middle class may make up 33% of the population, or around 60 million people

The middle class is expected to be a driving force behind the country's economic development. A wealthier middle class can positively impact economic growth. That explanation is particularly important in the developing world, where economists increasingly identify a middle-class household as one with enough income to survive such shocks as a spell of unemployment, a health emergency, or even the bankruptcy of a small business without a major or permanent decline in its living standard. Middle-class citizens deal with plenty of economic anxiety and stress, but they don’t worry about being able to pay next month’s rent, car loan installment, or credit card bill.

The size of a country’s middle class has significant economic and political implications. A large middle class increases the demand for domestic goods and services and helps fuel consumption-led growth. Middle-class parents have the resources to save and invest in their children’s education, building human capital for the country as a whole. And in the developing world, middle class peoples are able to take reasonable business risks, becoming investors as well as consumers and workers. In all these ways, the emergence of a middle class drives economic growth.

Having a large middle class is also critical for fostering good governance. Middle-class citizens want the stability and predictability that come from a political system that promotes fair competition, in which the very rich cannot rely on insider privileges to accumulate unearned wealth. Middle-class people are less vulnerable than the poor to pressure to pay into patronage networks and are more likely to support governments that protect private property and encourage private investment. When the middle class reaches a certain size perhaps 30 percent of the population is enough its members can start to identify with one another and to use their collective power to demand that the state spend their taxes to finance public services, security, and other critical public goods.

The point is that when it comes to the middle class, size matters, but it is not everything. For example, if a middle class grows large but then feels threatened during a major economic downturn, its members may succumb to demagogic and populist appeals from the right or the left. Put simply, to constitute a politically positive force, a middle class must be not only large relative to a country’s other classes but also prospering and feeling confident. That is not surprising that the behavioral studies show that for most people, losing ground is more troubling than never gaining it, a tendency known as “loss aversion.” Widespread fears of looming losses undermine the sense of security and the expectations of a better future that characterize the middle class.

In a few developing countries, such as India, Kenya, Nigeria, and Tanzania, middle classes have appeared but have not grown nearly large enough to effect significant political change. In those places, creating a virtuous cycle of middle-class growth and accountable governance remains a long-term development challenge. So although it makes sense to cheer the existence of modern shopping malls serving new middle classes in Lagos and Bangalore, it does not make sense to assume that every country with a lot of new malls is on a steady, predictable road to good governance and liberal democracy. Meanwhile, advances in communications technology—the Internet, mobile devices, and social media have empowered middle classes around the world to organize and advocate corporate and government accountability.

The fear is that the new middle classes will be hit hard if it turns out that global growth was built too much on easy credit and commodity booms and too little on the productivity gains that raise incomes and living standards for everyone. If the middle class and those struggling to join it see their incomes stagnate or fall, they are less likely to support the economic and regulatory policies that over time increase the size of the overall economic pie. Instead, they are likely to embrace short-term, populist measures they believe will help them retain their gains and meet their raised expectations. In short, slow growth (or, worse, an economic collapse) could erode middle-class support for good governance, a broad social contract, and the economic reforms that sustain the opportunities on which the middle class depends. In leaner times, however, a beleaguered middle class might be less tolerant of programs that benefit the poor and the working class and might politically ally itself with the rich instead. A similar shift could occur in every country with a large but relatively new middle class. It takes several decades to develop and solidify the responsive state institutions that the middle class wants and on which it relies.

Increasing rate of middle class income group has not been much but expected to increase if the demographic dividend is used well. So demographic dividend to increase the rate of middle class income group is an urgent need to drive consumption, create jobs, improve quality of services, increase tax revenue. Factors that can contribute to grow the middle class by improving the business environment, investing in skills, strengthening social protection, strengthening tax policies.

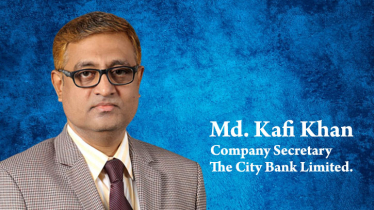

The writer is the company Secretary of City Bank PLC

Messenger/EHM